Only Living Culture Where The Female Body Was Adorned And Not Hidden But Worshipped

Ankit Gupta | May 03, 2025, 12:02 IST

India stands apart as perhaps the only living civilization where the female body was not shamed but adorned and worshipped—as a symbol of fertility, strength, and divinity. The goddesses were not covered up, but revered in their powerful, unashamed forms. Clothing was never about suppression, but about harmony with nature and comfort. Women's garments were designed for the tropical climate and freedom of movement—not to appease the insecurities or hormones of a few lustful men.

India’s ancient culture, deeply connected to its spiritual and philosophical roots, always held the female body in high regard. In stark contrast to the way many cultures view women’s bodies today—often as something to be hidden or modestly veiled—ancient India celebrated the female form as a manifestation of Shakti, the divine feminine power. Texts like the Rig Veda and artistic depictions in temples have consistently portrayed women as symbols of strength, fertility, and grace. The concept of the divine feminine was not just an abstraction but a core aspect of how the culture understood the universe. Female deities like Durga, Lakshmi, and Saraswati were not merely idols to be worshipped; they were the epitome of creative energy and cosmic power. It is in this context that the idea of modesty as we know it today becomes increasingly complex.

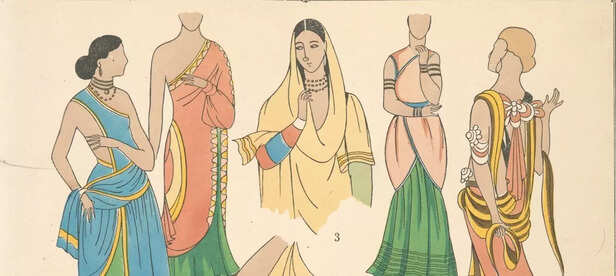

One of the striking features of pre-colonial and pre-Islamic India was how clothing, particularly for women, was designed not to suppress, but to adorn the body. This was not clothing made to appease the lustful gaze of men or hide what was considered ‘shameful’; it was functional, comfortable, and respectful of the body’s natural form. Garments like the saree, draped freely around the body, or the uttariya, a piece of cloth often knotted at the back, allowed women to express their beauty, freedom, and grace without constraint. The garments were designed with the climate in mind—loose, flowing, and suited to the warm, tropical conditions of India. They were not meant to cover or hide but rather to adorn the body in harmony with nature.

The concept of covering one’s upper body, a practice now ingrained in most cultures, was virtually absent in ancient India. Men and women alike often left their torsos uncovered, as evidenced in numerous ancient sculptures, paintings, and texts. Iconography and temple art, such as those found in Khajuraho, Ajanta, and Konark, depict gods and goddesses with bare torsos, celebrating the physical form without shame. Even in literature, the naked body was not viewed as an object of shame but as an expression of spiritual or aesthetic beauty. The Natya Shastra, an ancient Indian treatise on performing arts, speaks of the body as an instrument of expression, and in the performing arts, both male and female actors often performed with exposed upper bodies. This wasn’t a celebration of lust, but rather an embodiment of the energy and fluidity of life itself.

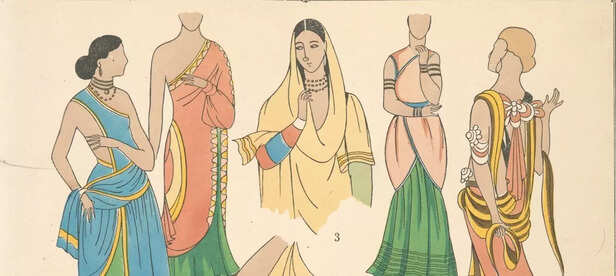

However, this era of freedom in clothing and body representation began to change with the advent of invasions and foreign rule. The first significant disruption occurred with the arrival of Central Asian Muslim invaders, including figures like Mahmud of Ghazni and later, the Mughal Empire. The image of the female body began to shift drastically, as women became vulnerable to violence, abduction, and exploitation. The fear and trauma of these invasions led to the imposition of more restrictive norms, including the practice of veiling, or ghoonghat, as a defensive measure. Women began to cover their heads and faces, not out of a cultural preference but as a means to protect themselves from being seen as sexual objects by invading forces. It was an act of survival, not tradition.

Further, the British colonial period cemented this cultural shift towards modesty and concealment. British colonizers, heavily influenced by Victorian ideals of femininity and modesty, sought to impose their standards on India. The colonial rulers not only pushed for physical modesty but also set the stage for a moralizing, restrictive view of Indian culture. The colonial elites, in an effort to mimic the British, adopted their own forms of modesty, and these norms seeped into the very fabric of Indian society. The once-proud tradition of celebrating the female body gave way to a culture of shame and suppression. Stitched clothing, including blouses and other items designed to cover the body, became a symbol of “respectability” in the eyes of both the colonial administration and local elites. What had once been a freely chosen cultural practice was now framed as a marker of social status and morality.

Over time, these new practices, which were born out of necessity and survival, became entrenched in society. As the generations passed, the origins of these customs were forgotten. The cultural memory of a time when women’s bodies were seen as sacred and celebrated faded, and the restrictive norms imposed by invaders and colonizers became synonymous with Indian tradition itself.

Yet, remnants of India’s original ethos remain. Ancient temples, especially those in Khajuraho and Konark, still bear witness to an era when the human body—particularly the female body—was celebrated without shame. The sculptures there, often depicting intricate scenes of eroticism and daily life, highlight the deep connection between physicality and spirituality in ancient Indian culture. These artworks were not pornographic; they were part of the sacred space, meant to reflect the divinity that pervades all aspects of life, including sensuality. The sexual energy was understood not as something profane but as a manifestation of divine creation.

The saree, which is still worn in many parts of India today, stands as the last survivor of this unbroken tradition. Though modern interpretations of modesty have altered the way it is worn, the saree is a symbol of the freedom and grace that once defined Indian clothing. Its unstitched form is a tribute to the fluidity and adaptability of the human body. It was never meant to restrict, but to adorn. The saree’s versatility in draping and style mirrors the ease with which ancient Indian women moved through their lives. The blouse, a later addition in response to colonial influence, is a modern interpretation of a garment that was once free-flowing and unencumbered.

It is time to reclaim this narrative. The restrictive modesty that was imposed upon Indian women through foreign invasions and colonial rule is not the essence of Indian culture. Modesty and shame were never the original ideals; adornment, freedom, and celebration were. The female body was not something to hide, but to honour. To return to the roots of this ancient practice is not a call for regression but a revival of wisdom—an opportunity to reconnect with the dignity, freedom, and strength of Indian culture.

India must remember that it was once a civilization where the female body was not hidden behind layers of fabric or shame but adorned in ways that celebrated life, love, and divinity. The cultural amnesia created by invasions and colonisation has led us to forget what was once a universal truth—that the female form is a temple of Shakti, deserving of reverence, not repression.

Thus, reclaiming the ancient vision of the female body is a powerful act of spiritual and cultural revival. Women’s bodies should be allowed to be temples of power and grace once again. Adornment, not concealment, is the true legacy of Indian culture. It is a legacy that celebrates life in all its forms and honours the divine feminine energy that resides in every woman. We must remember that the female body, in all its beauty and complexity, is not an object of shame but an embodiment of divine power. It is time to return to a culture that adorns, not hides.

The Sacred Celebration of the Female Body in Ancient India

Image Credit: Pixabay

One of the striking features of pre-colonial and pre-Islamic India was how clothing, particularly for women, was designed not to suppress, but to adorn the body. This was not clothing made to appease the lustful gaze of men or hide what was considered ‘shameful’; it was functional, comfortable, and respectful of the body’s natural form. Garments like the saree, draped freely around the body, or the uttariya, a piece of cloth often knotted at the back, allowed women to express their beauty, freedom, and grace without constraint. The garments were designed with the climate in mind—loose, flowing, and suited to the warm, tropical conditions of India. They were not meant to cover or hide but rather to adorn the body in harmony with nature.

The concept of covering one’s upper body, a practice now ingrained in most cultures, was virtually absent in ancient India. Men and women alike often left their torsos uncovered, as evidenced in numerous ancient sculptures, paintings, and texts. Iconography and temple art, such as those found in Khajuraho, Ajanta, and Konark, depict gods and goddesses with bare torsos, celebrating the physical form without shame. Even in literature, the naked body was not viewed as an object of shame but as an expression of spiritual or aesthetic beauty. The Natya Shastra, an ancient Indian treatise on performing arts, speaks of the body as an instrument of expression, and in the performing arts, both male and female actors often performed with exposed upper bodies. This wasn’t a celebration of lust, but rather an embodiment of the energy and fluidity of life itself.

Invasions and Colonial Influence

Shift from Freedom to Suppression ( Image Credit: pixels)

However, this era of freedom in clothing and body representation began to change with the advent of invasions and foreign rule. The first significant disruption occurred with the arrival of Central Asian Muslim invaders, including figures like Mahmud of Ghazni and later, the Mughal Empire. The image of the female body began to shift drastically, as women became vulnerable to violence, abduction, and exploitation. The fear and trauma of these invasions led to the imposition of more restrictive norms, including the practice of veiling, or ghoonghat, as a defensive measure. Women began to cover their heads and faces, not out of a cultural preference but as a means to protect themselves from being seen as sexual objects by invading forces. It was an act of survival, not tradition.

Further, the British colonial period cemented this cultural shift towards modesty and concealment. British colonizers, heavily influenced by Victorian ideals of femininity and modesty, sought to impose their standards on India. The colonial rulers not only pushed for physical modesty but also set the stage for a moralizing, restrictive view of Indian culture. The colonial elites, in an effort to mimic the British, adopted their own forms of modesty, and these norms seeped into the very fabric of Indian society. The once-proud tradition of celebrating the female body gave way to a culture of shame and suppression. Stitched clothing, including blouses and other items designed to cover the body, became a symbol of “respectability” in the eyes of both the colonial administration and local elites. What had once been a freely chosen cultural practice was now framed as a marker of social status and morality.

Over time, these new practices, which were born out of necessity and survival, became entrenched in society. As the generations passed, the origins of these customs were forgotten. The cultural memory of a time when women’s bodies were seen as sacred and celebrated faded, and the restrictive norms imposed by invaders and colonizers became synonymous with Indian tradition itself.

Reclaiming the Legacy

Adornment Over Concealment

Yet, remnants of India’s original ethos remain. Ancient temples, especially those in Khajuraho and Konark, still bear witness to an era when the human body—particularly the female body—was celebrated without shame. The sculptures there, often depicting intricate scenes of eroticism and daily life, highlight the deep connection between physicality and spirituality in ancient Indian culture. These artworks were not pornographic; they were part of the sacred space, meant to reflect the divinity that pervades all aspects of life, including sensuality. The sexual energy was understood not as something profane but as a manifestation of divine creation.

The saree, which is still worn in many parts of India today, stands as the last survivor of this unbroken tradition. Though modern interpretations of modesty have altered the way it is worn, the saree is a symbol of the freedom and grace that once defined Indian clothing. Its unstitched form is a tribute to the fluidity and adaptability of the human body. It was never meant to restrict, but to adorn. The saree’s versatility in draping and style mirrors the ease with which ancient Indian women moved through their lives. The blouse, a later addition in response to colonial influence, is a modern interpretation of a garment that was once free-flowing and unencumbered.

It is time to reclaim this narrative. The restrictive modesty that was imposed upon Indian women through foreign invasions and colonial rule is not the essence of Indian culture. Modesty and shame were never the original ideals; adornment, freedom, and celebration were. The female body was not something to hide, but to honour. To return to the roots of this ancient practice is not a call for regression but a revival of wisdom—an opportunity to reconnect with the dignity, freedom, and strength of Indian culture.

India must remember that it was once a civilization where the female body was not hidden behind layers of fabric or shame but adorned in ways that celebrated life, love, and divinity. The cultural amnesia created by invasions and colonisation has led us to forget what was once a universal truth—that the female form is a temple of Shakti, deserving of reverence, not repression.

Thus, reclaiming the ancient vision of the female body is a powerful act of spiritual and cultural revival. Women’s bodies should be allowed to be temples of power and grace once again. Adornment, not concealment, is the true legacy of Indian culture. It is a legacy that celebrates life in all its forms and honours the divine feminine energy that resides in every woman. We must remember that the female body, in all its beauty and complexity, is not an object of shame but an embodiment of divine power. It is time to return to a culture that adorns, not hides.