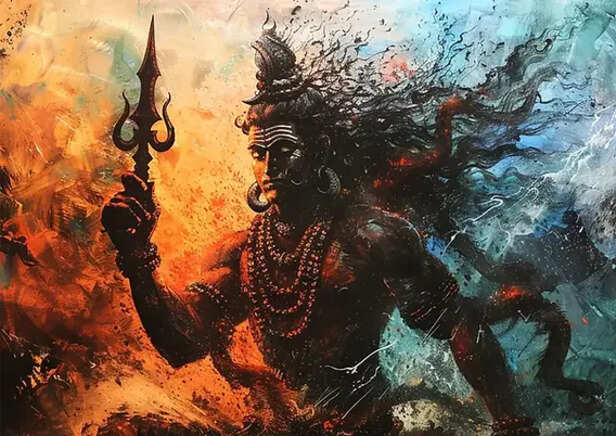

The Five Obstacles Between You and Shiva—A Journey Through the Kleshas

Ankit Gupta | Apr 15, 2025, 08:54 IST

In the ancient yogic tradition, the journey to realizing Shiva—the pure, undivided Consciousness—is not outward, but inward. Yet, five subtle veils obscure this inner light. These are the pancha kleshas, the five afflictions that keep the soul entangled in illusion (Maya) and far from liberation (moksha). It delves into the five fundamental obstacles—Avidya (ignorance), Asmita (egoism), Raga (attachment), Dvesha (aversion), and Abhinivesha (fear of death)—that block the path to realizing Shiva, the Supreme Self.

The ancient yogic texts reveal a profound truth: the divine is not somewhere distant, hidden in the clouds or locked in celestial realms—it is within us. Shiva, the supreme consciousness, the unchanging, the witness beyond time, is not separate from us but veiled by the very constructs we unknowingly nurture. The separation we feel is an illusion, sustained by five subtle afflictions that the sages of old identified with crystalline precision. These afflictions are called kleshas—mental-emotional obstacles that distort our perception and keep us trapped in samsara, the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. In their raw essence, these five—Avidya, Asmita, Raga, Dvesha, and Abhinivesha—form the wall between the seeker and Shiva. Understanding and transcending them is the beginning of freedom.

Avidya – The Primordial

At the root of all spiritual confusion lies Avidya, often translated as ignorance, but far more dangerous than mere lack of knowledge. Avidya is the fundamental misapprehension of reality—it is mistaking the impermanent for the permanent, the impure for the pure, the painful for the pleasurable, and the non-self (anatman) for the Self (Atman). This delusion forms the basis of all suffering.

When a person identifies with the body, thinking “this is me,” they unknowingly lay the foundation for pain. The body changes, decays, ages, and dies—yet we cling to it as the center of our being. When the mind fluctuates with emotion or the ego rises with pride, we assume this temporary experience defines our entire existence. This is Avidya: the original sin of misidentification. The sages insist that the Atman—the true Self—is untouched by these fluctuations. It is eternal, luminous, and one with Brahman, the all-encompassing consciousness.

But how does Avidya arise? It is not an event but a condition. Like mud settling in the bottom of a lake, it obscures the clarity of water. The lake still reflects the sky, but the reflection is distorted. Similarly, Avidya clouds our perception, making us forget our divine origin. The Gita confirms this when Krishna says, “These bodies come to an end; but that vast embodied Self is ageless, fathomless, eternal.” Yet, under Avidya’s spell, we mourn death, fear loss, and chase fleeting joys. The solution lies in knowledge—not academic, but jnana, the direct realization of truth through meditation, introspection, and grace.

From Avidya springs Asmita—the ego sense, the false “I.” It is the erroneous identification of the Self with the mind, body, or role. If Avidya is the mud in the lake, Asmita is the belief that the reflections on the water's surface are reality itself. The ego says, “I am my thoughts,” “I am my profession,” “I am my success or failure,” and in doing so, shrinks the infinite Self into a fleeting form.

Asmita is subtle and insidious. It builds a fortress of individuality, separating the soul from the cosmos. Where there is ego, there is duality. Where there is duality, there is fear, craving, jealousy, and division. We believe we are isolated entities in competition with others for significance, security, and survival. The truth, however, is vastly different. When the ego drops, one sees the entire universe as one’s own body. Shiva does not operate from ego; he dissolves it. He is the stillness that exists beyond the wave of individuality.

Asmita is often reinforced by societal conditioning. We are taught to achieve, compare, and define ourselves through titles, appearances, and accolades. Even spiritual identity—“I am a yogi,” “I am enlightened”—can be a subtle form of ego. In deep meditation, when the ego dissolves, the seeker experiences turiya, the fourth state beyond waking, dreaming, and sleep. This state is egoless awareness—pure Shiva.

Where there is ego, there is desire. Raga is attachment to pleasure, to people, to objects that once brought satisfaction. It arises from memory—smriti—that retains the imprint of past joy and seeks its repetition. Raga is not simply desire; it is clinging, grasping, and binding the mind to external forms in the hope of happiness.

At a practical level, Raga manifests as addiction, obsession, and emotional dependence. We become attached to relationships, wealth, status, or even ideas. Yet all these are impermanent. The pleasure we seek through them is fleeting, and when they change or vanish—as all things do—pain follows. The deeper trap is that Raga creates an illusion: that our joy lies outside of us. In truth, joy is our natural state, and Shiva is the embodiment of bliss—not the pleasure of the senses, but the unshakable ecstasy of unity with all.

Raga creates ripples on the surface of the mind-lake. These ripples distort the reflection of the Self. The more attached we are to fleeting things, the more turbulent the mind becomes. Meditation becomes difficult, inner stillness impossible. True detachment is not renunciation of life, but the freedom from needing life to be a certain way. When a seeker lets go of Raga, the heart becomes light, and Shiva dances there.

If Raga is clinging to pleasure, Dvesha is the repulsion from pain. It is the avoidance, hatred, or fear of experiences, people, or emotions that caused suffering in the past. Just as Raga chains us to desire, Dvesha binds us to fear and resentment. It keeps the mind restless, agitated, and filled with judgment.

Every time we resist discomfort, avoid confrontation, or suppress unpleasant emotions, we strengthen Dvesha. It is born of memory, just like Raga, but carries a negative charge. For example, someone betrayed in a relationship may develop aversion to vulnerability. One who failed in a venture may avoid risk. These aversions may seem protective but often limit growth and insight.

Spiritually, Dvesha blocks compassion and neutrality. It makes the seeker judge others, resist life's lessons, and avoid the very situations that can lead to liberation. The Gita teaches samatvam—evenness of mind in pleasure and pain—as the essence of yoga. Shiva sits in cremation grounds not to glorify death, but to show that he is untouched by either pleasure or pain. He is the witness that embraces all without preference.

To overcome Dvesha, one must practice pratipaksha bhavana—consciously cultivating the opposite. Where there is hatred, sow love. Where there is resistance, practice surrender. Over time, the aversive tendencies dissolve, and the inner lake begins to still.

Perhaps the most deeply embedded of all kleshas is Abhinivesha—the clinging to life and the fear of death. This fear exists even in the wise, as Patanjali notes. It is instinctual, arising not just from the ego, but from the very structure of existence rooted in duality. Abhinivesha is not simply fear of physical death; it is fear of loss, change, annihilation, and the unknown.

Despite knowing intellectually that death is inevitable, most people live in denial of it. We seek security in insurance, in relationships, in beliefs, hoping to make life predictable. But death is the ultimate unpredictability. It reminds us that we are not in control. The spiritual path invites us to confront this fear, not with morbidity, but with awareness.

Shiva, as Mahakala—the Lord of Time—is the destroyer of this fear. He wears the garland of skulls, not to terrify, but to liberate. In his dance of Tandava, destruction is not an end, but a doorway to transformation. The seeker who accepts death as a passage and sees the soul as eternal transcends Abhinivesha. Fear becomes awe. Mortality becomes a myth.

Even spiritually advanced beings may feel fear when the ego resists dissolution. But meditation, mantra, and surrender slowly erode the clinging. The Maha Mrityunjaya Mantra—“Tryambakam Yajamahe…”—is a powerful invocation to transcend the grip of death and awaken the undying Self within.

To make sense of these kleshas, imagine a still lake. At its bottom lies Avidya, the mud that clouds the water. Floating on its surface is Asmita, the illusion that the shifting reflections are the real Self. The wind that stirs the water represents Raga and Dvesha, the ripples of desire and aversion that disturb clarity. And Abhinivesha is the fear that the lake will one day dry up.

When the wind ceases, the mud settles, and the water becomes transparent. In that stillness, one sees the sky, the sun, the stars—clear and undistorted. Likewise, when the mind is stilled through discipline, self-inquiry, and grace, the seeker sees Shiva—Satyam Shivam Sundaram—Truth, Consciousness, and Beauty.

The sacred mantra “Aum Namah Shivaya” is more than a chant. It is a vibration that dissolves the five kleshas. “Aum” represents the eternal sound, the substratum of the universe. “Namah” is surrender—the dissolving of ego. “Shivaya” invokes the auspicious, the one who liberates.

When chanted with awareness, this mantra becomes a bridge across illusion. It purifies ignorance (Avidya), humbles the ego (Asmita), loosens desire (Raga), softens resistance (Dvesha), and melts fear (Abhinivesha). The five syllables of Shivaya (Na-Ma-Shi-Va-Ya) are sometimes said to represent the five elements—earth, water, fire, air, and ether—thus dissolving the five sheaths of the body and merging the seeker with the Self.

The journey to Shiva is not upward, but inward. Each of these five obstacles is a veil,In the ancient yogic tradition, the journey to realizing Shiva—the pure, undivided Consciousness—is not outward, but inward. Yet, five subtle veils obscure this inner light. These are the pancha kleshas, the five afflictions that keep the soul entangled in illusion (Maya) and far from liberation (moksha). not a wall. They can be lifted through awareness, practice, and devotion. The path is not always easy. These afflictions have roots in lifetimes of conditioning. But each step into silence, each breath taken in mindfulness, each moment of surrender brings one closer to the truth.

Shiva is not a distant deity. He is the stillness within your breath, the silence between your thoughts, the awareness watching your experiences. When the kleshas dissolve, there is nothing separating you from him. You do not become Shiva—you remember you were always That.

Let the mud settle. Let the lake become still. Let the reflection reveal the Infinite.

Avidya – The Primordial Ignorance

Ignorance

At the root of all spiritual confusion lies Avidya, often translated as ignorance, but far more dangerous than mere lack of knowledge. Avidya is the fundamental misapprehension of reality—it is mistaking the impermanent for the permanent, the impure for the pure, the painful for the pleasurable, and the non-self (anatman) for the Self (Atman). This delusion forms the basis of all suffering.

When a person identifies with the body, thinking “this is me,” they unknowingly lay the foundation for pain. The body changes, decays, ages, and dies—yet we cling to it as the center of our being. When the mind fluctuates with emotion or the ego rises with pride, we assume this temporary experience defines our entire existence. This is Avidya: the original sin of misidentification. The sages insist that the Atman—the true Self—is untouched by these fluctuations. It is eternal, luminous, and one with Brahman, the all-encompassing consciousness.

But how does Avidya arise? It is not an event but a condition. Like mud settling in the bottom of a lake, it obscures the clarity of water. The lake still reflects the sky, but the reflection is distorted. Similarly, Avidya clouds our perception, making us forget our divine origin. The Gita confirms this when Krishna says, “These bodies come to an end; but that vast embodied Self is ageless, fathomless, eternal.” Yet, under Avidya’s spell, we mourn death, fear loss, and chase fleeting joys. The solution lies in knowledge—not academic, but jnana, the direct realization of truth through meditation, introspection, and grace.

Asmita – The Illusion of I

Illusion of the Self

From Avidya springs Asmita—the ego sense, the false “I.” It is the erroneous identification of the Self with the mind, body, or role. If Avidya is the mud in the lake, Asmita is the belief that the reflections on the water's surface are reality itself. The ego says, “I am my thoughts,” “I am my profession,” “I am my success or failure,” and in doing so, shrinks the infinite Self into a fleeting form.

Asmita is subtle and insidious. It builds a fortress of individuality, separating the soul from the cosmos. Where there is ego, there is duality. Where there is duality, there is fear, craving, jealousy, and division. We believe we are isolated entities in competition with others for significance, security, and survival. The truth, however, is vastly different. When the ego drops, one sees the entire universe as one’s own body. Shiva does not operate from ego; he dissolves it. He is the stillness that exists beyond the wave of individuality.

Asmita is often reinforced by societal conditioning. We are taught to achieve, compare, and define ourselves through titles, appearances, and accolades. Even spiritual identity—“I am a yogi,” “I am enlightened”—can be a subtle form of ego. In deep meditation, when the ego dissolves, the seeker experiences turiya, the fourth state beyond waking, dreaming, and sleep. This state is egoless awareness—pure Shiva.

Raga – The Chain of Attachment

Rage

Where there is ego, there is desire. Raga is attachment to pleasure, to people, to objects that once brought satisfaction. It arises from memory—smriti—that retains the imprint of past joy and seeks its repetition. Raga is not simply desire; it is clinging, grasping, and binding the mind to external forms in the hope of happiness.

At a practical level, Raga manifests as addiction, obsession, and emotional dependence. We become attached to relationships, wealth, status, or even ideas. Yet all these are impermanent. The pleasure we seek through them is fleeting, and when they change or vanish—as all things do—pain follows. The deeper trap is that Raga creates an illusion: that our joy lies outside of us. In truth, joy is our natural state, and Shiva is the embodiment of bliss—not the pleasure of the senses, but the unshakable ecstasy of unity with all.

Raga creates ripples on the surface of the mind-lake. These ripples distort the reflection of the Self. The more attached we are to fleeting things, the more turbulent the mind becomes. Meditation becomes difficult, inner stillness impossible. True detachment is not renunciation of life, but the freedom from needing life to be a certain way. When a seeker lets go of Raga, the heart becomes light, and Shiva dances there.

Dvesha – The Shadow of Aversion

Source: Freepik

If Raga is clinging to pleasure, Dvesha is the repulsion from pain. It is the avoidance, hatred, or fear of experiences, people, or emotions that caused suffering in the past. Just as Raga chains us to desire, Dvesha binds us to fear and resentment. It keeps the mind restless, agitated, and filled with judgment.

Every time we resist discomfort, avoid confrontation, or suppress unpleasant emotions, we strengthen Dvesha. It is born of memory, just like Raga, but carries a negative charge. For example, someone betrayed in a relationship may develop aversion to vulnerability. One who failed in a venture may avoid risk. These aversions may seem protective but often limit growth and insight.

Spiritually, Dvesha blocks compassion and neutrality. It makes the seeker judge others, resist life's lessons, and avoid the very situations that can lead to liberation. The Gita teaches samatvam—evenness of mind in pleasure and pain—as the essence of yoga. Shiva sits in cremation grounds not to glorify death, but to show that he is untouched by either pleasure or pain. He is the witness that embraces all without preference.

To overcome Dvesha, one must practice pratipaksha bhavana—consciously cultivating the opposite. Where there is hatred, sow love. Where there is resistance, practice surrender. Over time, the aversive tendencies dissolve, and the inner lake begins to still.

Abhinivesha – The Fear of Death

Conquer the Death

Perhaps the most deeply embedded of all kleshas is Abhinivesha—the clinging to life and the fear of death. This fear exists even in the wise, as Patanjali notes. It is instinctual, arising not just from the ego, but from the very structure of existence rooted in duality. Abhinivesha is not simply fear of physical death; it is fear of loss, change, annihilation, and the unknown.

Despite knowing intellectually that death is inevitable, most people live in denial of it. We seek security in insurance, in relationships, in beliefs, hoping to make life predictable. But death is the ultimate unpredictability. It reminds us that we are not in control. The spiritual path invites us to confront this fear, not with morbidity, but with awareness.

Shiva, as Mahakala—the Lord of Time—is the destroyer of this fear. He wears the garland of skulls, not to terrify, but to liberate. In his dance of Tandava, destruction is not an end, but a doorway to transformation. The seeker who accepts death as a passage and sees the soul as eternal transcends Abhinivesha. Fear becomes awe. Mortality becomes a myth.

Even spiritually advanced beings may feel fear when the ego resists dissolution. But meditation, mantra, and surrender slowly erode the clinging. The Maha Mrityunjaya Mantra—“Tryambakam Yajamahe…”—is a powerful invocation to transcend the grip of death and awaken the undying Self within.

The Lake and the Reflection – A Practical Analogy

When the wind ceases, the mud settles, and the water becomes transparent. In that stillness, one sees the sky, the sun, the stars—clear and undistorted. Likewise, when the mind is stilled through discipline, self-inquiry, and grace, the seeker sees Shiva—Satyam Shivam Sundaram—Truth, Consciousness, and Beauty.

Aum Namah Shivaya – The Mantra of Dissolution

When chanted with awareness, this mantra becomes a bridge across illusion. It purifies ignorance (Avidya), humbles the ego (Asmita), loosens desire (Raga), softens resistance (Dvesha), and melts fear (Abhinivesha). The five syllables of Shivaya (Na-Ma-Shi-Va-Ya) are sometimes said to represent the five elements—earth, water, fire, air, and ether—thus dissolving the five sheaths of the body and merging the seeker with the Self.

The Journey Inward

Shiva is not a distant deity. He is the stillness within your breath, the silence between your thoughts, the awareness watching your experiences. When the kleshas dissolve, there is nothing separating you from him. You do not become Shiva—you remember you were always That.

Let the mud settle. Let the lake become still. Let the reflection reveal the Infinite.